The Operator’s Edge: Adaptive Company Cultures For Our Transformative Times

Mastering AI and Adaptive Cultures in the Era of the Company of One

New to Operating?

Check out these reader favorites:

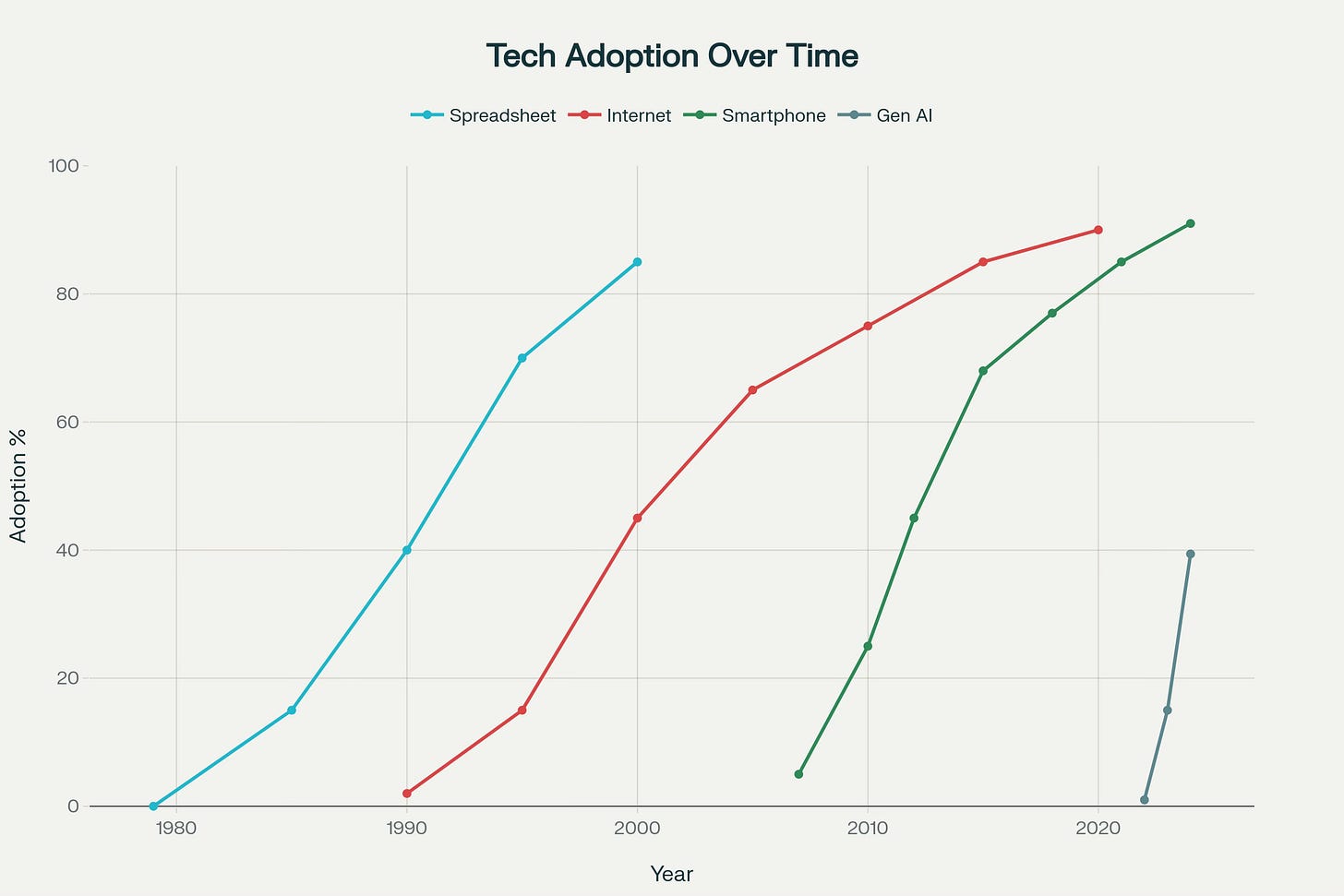

Every generation of operators inherits a new computer. Spreadsheets, the internet, smartphones. And now, AI. The question isn’t whether it works. The question is whether we will.

Introduction: The New Computer

We're living through the most overhyped and underestimated technological shift in history. Yes, AI is transformative. Yes, the tools are improving exponentially. Yes, the capital deployment is unprecedented. But the greatest fiction of the current moment isn't about what AI can do, it's about how fast it can do it. And that fiction is creating a crisis for the operators tasked with delivering on these impossible timelines. MIT and McKinsey both estimate that 95% of generative AI projects fail to reach production, not because the models don’t work, but because organizations cannot absorb them (Substack – The Bridge to Our Future Success). Workflows are jamming, resistance is taking hold, and leaders are chasing experiments untethered from strategy.

We’ve seen this before. Each new “computer”—the spreadsheet, the internet, the smartphone—promised efficiency, but the advantage always went to those who could design systems and cultures that made the tools useful. AI is no different. It’s a new computer.

When set against the baseline for awe-inspired that we developed when Chat first hit, and Nvidia became a household name, large language models may have captured headlines, but their progress is slowing. Newer models, once heralded as “God-like,” are starting to feel like routine software updates. At the same time, smaller, specialized models are proving more practical. They are cheaper to run, easier to deploy, and often better suited for business use. As one IBM researcher put it, “your HR chatbot doesn’t need to know advanced physics” (The Economist).

Size and power matter less than fit and discipline. Just as companies did not need mainframes on every desk, today they do not need unique LLM’s, or even agents, for every workflow. The operating edge is not about access to technology but the ability to integrate it into repeatable, common sense processes that human teams can competently direct.

Lessons from Operating History

The foundations of operating strategy explain why technology alone never delivers the full competitive advantage we initially imagine. Ronald Coase described firms as cost-minimizing structures, expanding or contracting depending on whether coordination inside the firm was cheaper than in the open market. Alfred Chandler showed that the structures of our organizations must be adapted from strategy and that the strategies must align with working capacities. When DuPont adopted the multidivisional form in the early 20th century, it was because the complexity of new products demanded it. Andy Grove sharpened the point:

“You cannot delegate understanding.”

His Breakfast Factory model remains the clearest way to show that bottlenecks define output. The pace of the entire factory hinges not on the number of eggs or slices of toast available, but on the slowest station in the line. No amount of overproduction elsewhere can compensate if the bottleneck step isn’t addressed, which is why operators must constantly measure, rebalance, and redesign workflows to unlock capacity. Teams need to be sure that the work they’re doing is actually generating more productive capacity, not simply highlighting the new computer’s increased capacity.

The spreadsheet revolution of the 1980s illustrates this pattern. VisiCalc and later Excel gave small businesses financial sophistication once reserved for corporate giants. But only firms that redesigned reporting systems and trained staff to use spreadsheets correctly gained the advantage. The internet offered global reach, but companies like Amazon succeeded because they rebuilt logistics and culture around the web, while others who simply bolted on websites faded. The smartphone collapsed work and leisure into one device, but only firms that restructured workflows for mobile-first customers (and leaders), like Uber, capitalized.

The pattern is unmistakable: transformative technologies create winners only among those willing to transform themselves. AI represents the most dramatic test of this principle yet. Companies clinging to AI as a productivity enhancer for existing processes are repeating the mistakes of every failed digital transformation before them. Just as DuPont couldn't have dominated without restructuring for multidivisional complexity, and Amazon couldn't have won by simply adding e-commerce to traditional retail, today's leaders won't succeed by grafting AI onto yesterday's workflows. The competitive advantage lies not in the technology itself, but in the courage to reimagine what a company can become. Those who understand this will define the next era of business.

Technology adoption follows an S-curve: innovators and early adopters lead, but true impact arrives when the early and late majority absorb the change into everyday workflows.

Technology Without Culture Breaks

Goldman Sachs recently rolled out an AI assistant to all 46,000 employees. Partners describe saving hours each week on drafting documents, analysis, and translation. Yet they also warn of the risk of over-reliance. As one senior banker put it, “AI is a tool and not the source of truth…we need to continue to focus on individual accountability” (Financial Times).

This is Grove’s principle in practice: you cannot delegate understanding. Tools accelerate work, but judgment remains the scarce input. Operators must embed systems that make these new computers useful while keeping decision rights and accountability squarely human.

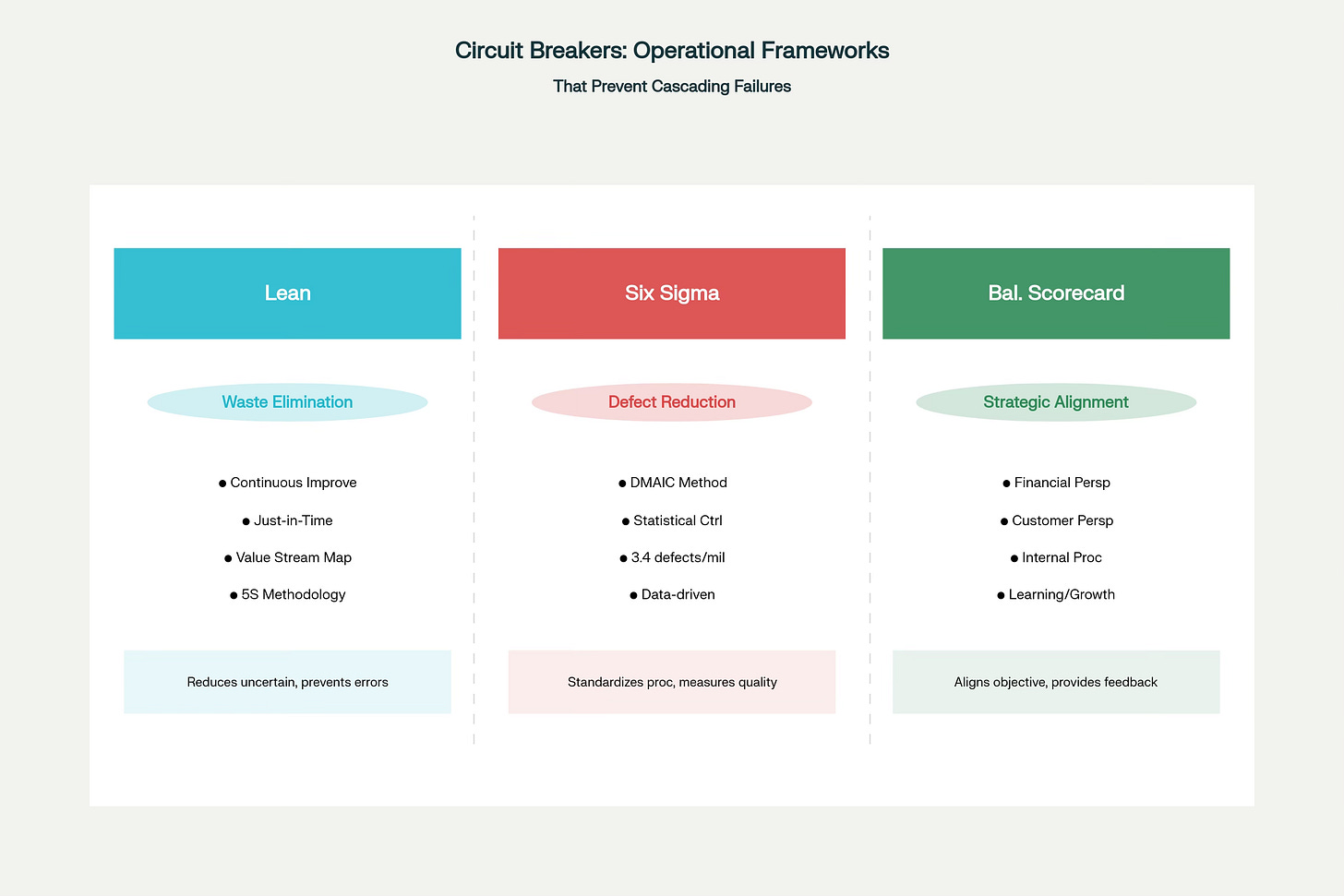

Operational frameworks supply the discipline. Lean, Six Sigma, and the Balanced Scorecard work as circuit breakers. They standardize, measure, and align, reducing uncertainty and preventing cascading errors. Complexity studies shows how small model failures can ripple into “avalanche effects.” With guardrails, volatility becomes feedback. Without them, firms become brittle.

Frameworks like Lean and the Balanced Scorecard act as circuit breakers in complex systems, preventing minor errors from cascading into failure.

Culture as Operating System

Leaders often announce culture change but deliver little. Inertia, not technology, is the stronger force. Studies of failed transformations show that it is visible behavior, not slogans, that shifts culture. When Octopus Energy reorganized its customer teams into autonomous units, or when Jamba Juice rebuilt its strategy by auditing values with staff and investors, the culture changed because actions changed (Financial Times).

Contrast this with the annual performance review. As The Economist satirized, it has become “Ann”—part of the furniture, disliked but immovable (The Economist). Netflix saw this problem years ago and abandoned annual reviews altogether, replacing them with continuous 360-degree feedback. That move wasn’t about perks but about embedding performance into the culture of everyday work.

This distinction matters for AI adoption. Systems and workflows, not mission statements, determine whether technology takes root. Operators must design documentation, training, and inspection routines that ensure behavior evolves with the tools.

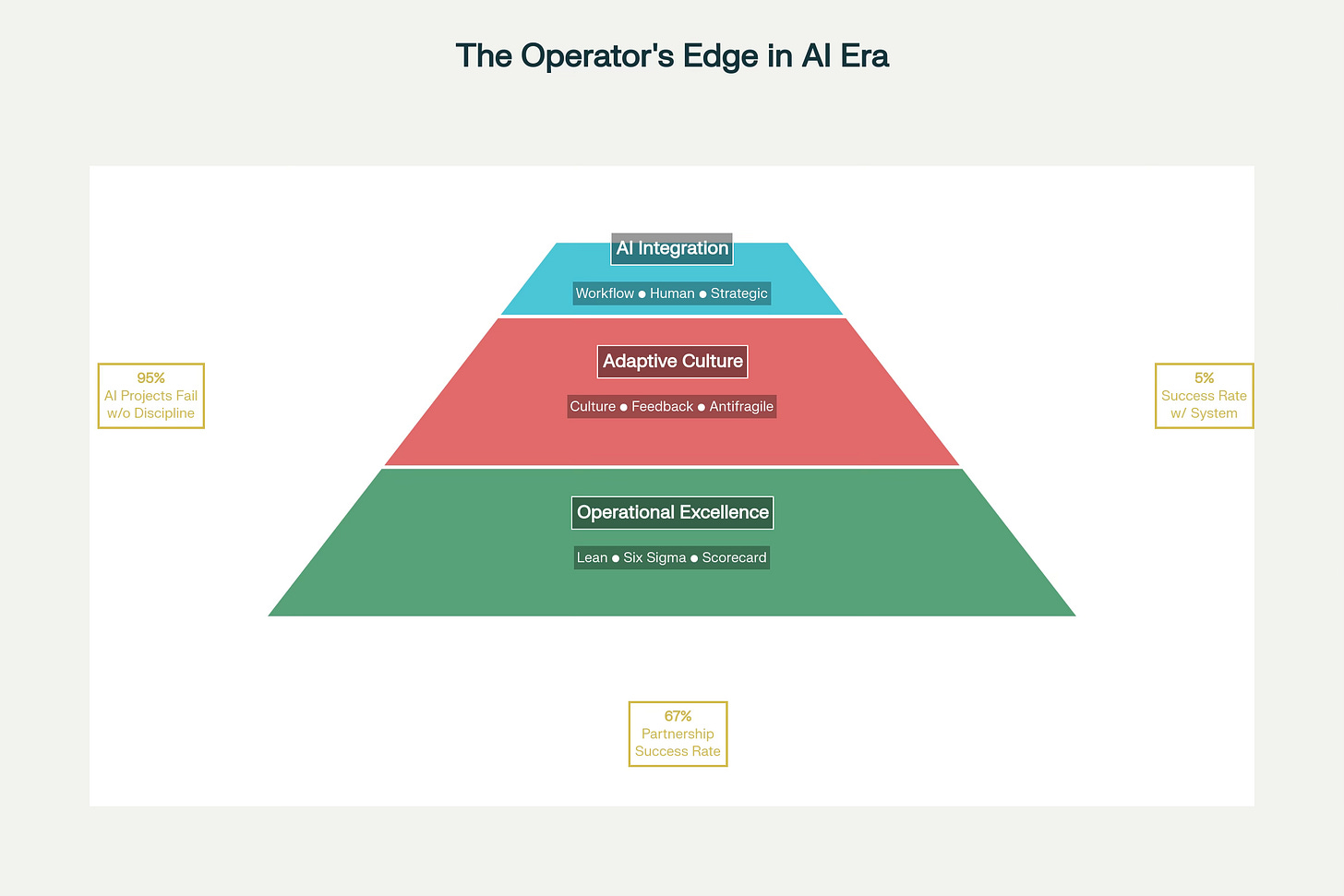

The Operator’s Edge rests on a layered foundation: technology, workflows, culture, and judgment. Each layer supports the one above it.

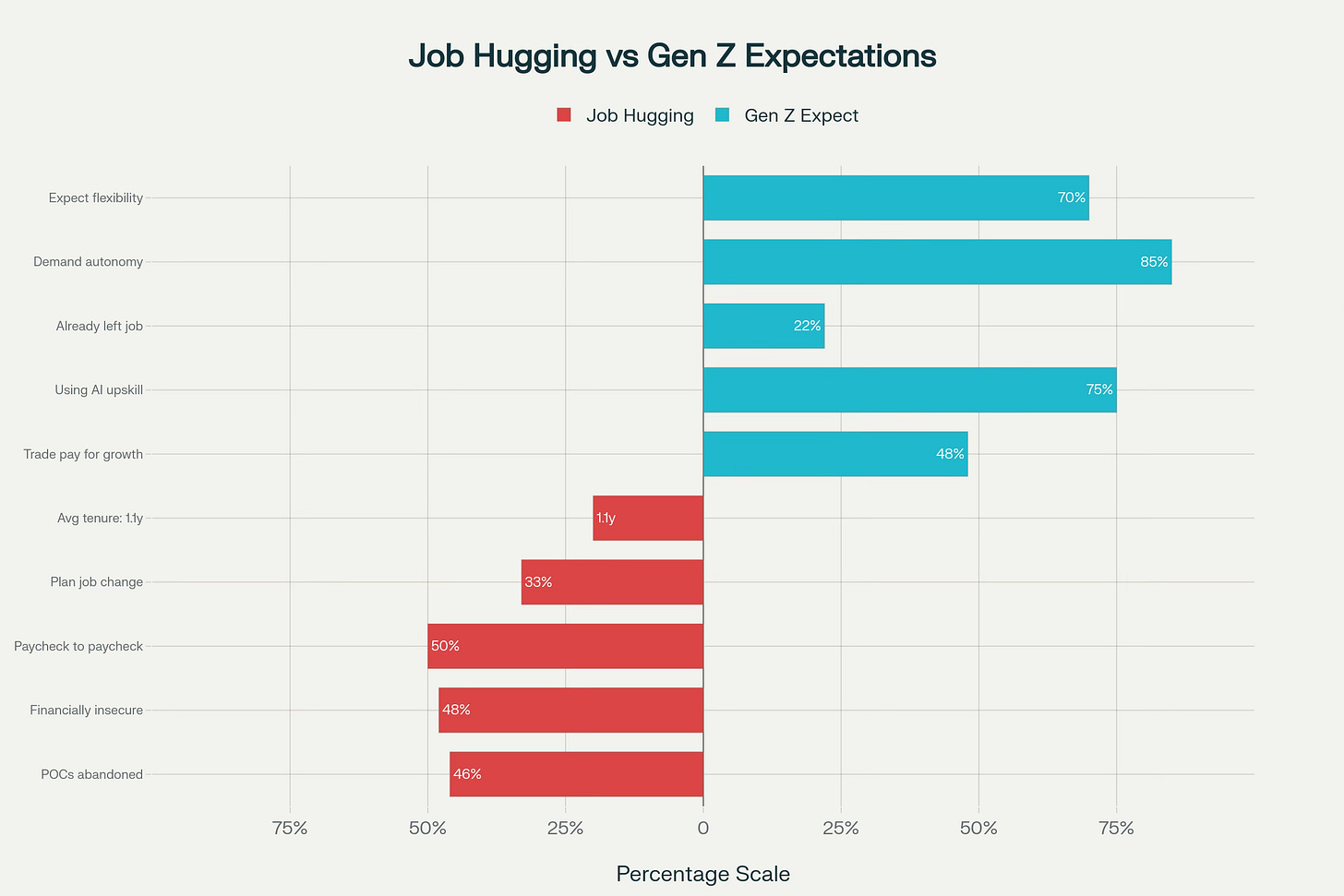

Sidenote: The Workforce Imperative

A tighter labor market has shifted worker behavior. Many employees are now “job hugging,” reluctant to move even when dissatisfied, a reversal of the job-hopping trend that defined the last decade (Wall Street Journal). At the same time, younger workers, especially Gen Z, expect flexibility, autonomy, and rapid development. Nearly half would trade pay for growth opportunities (Financial Times).

Operators must build systems that accommodate both realities: a workforce that clings to security and one that demands rapid change. This means investing in upskilling, designing multigenerational teams, and embedding continuous feedback. Reverse mentorship programs, hybrid options, and cross-generational project teams are practical mechanisms. Apple’s approach to on-device AI offers a parallel lesson. It did not chase the largest models but designed smaller, embedded systems for real users. Operators must do the same with human capital: design systems around practical needs, not hype. They must use our new computers to enable these success-centric cultural norms and expectations to persist if talent is to stay put and feel appreciated for the value they bring.

The operator economy is fragmenting traditional roles into networks of micro-enterprises and individual operators.

From Resilience to Antifragility

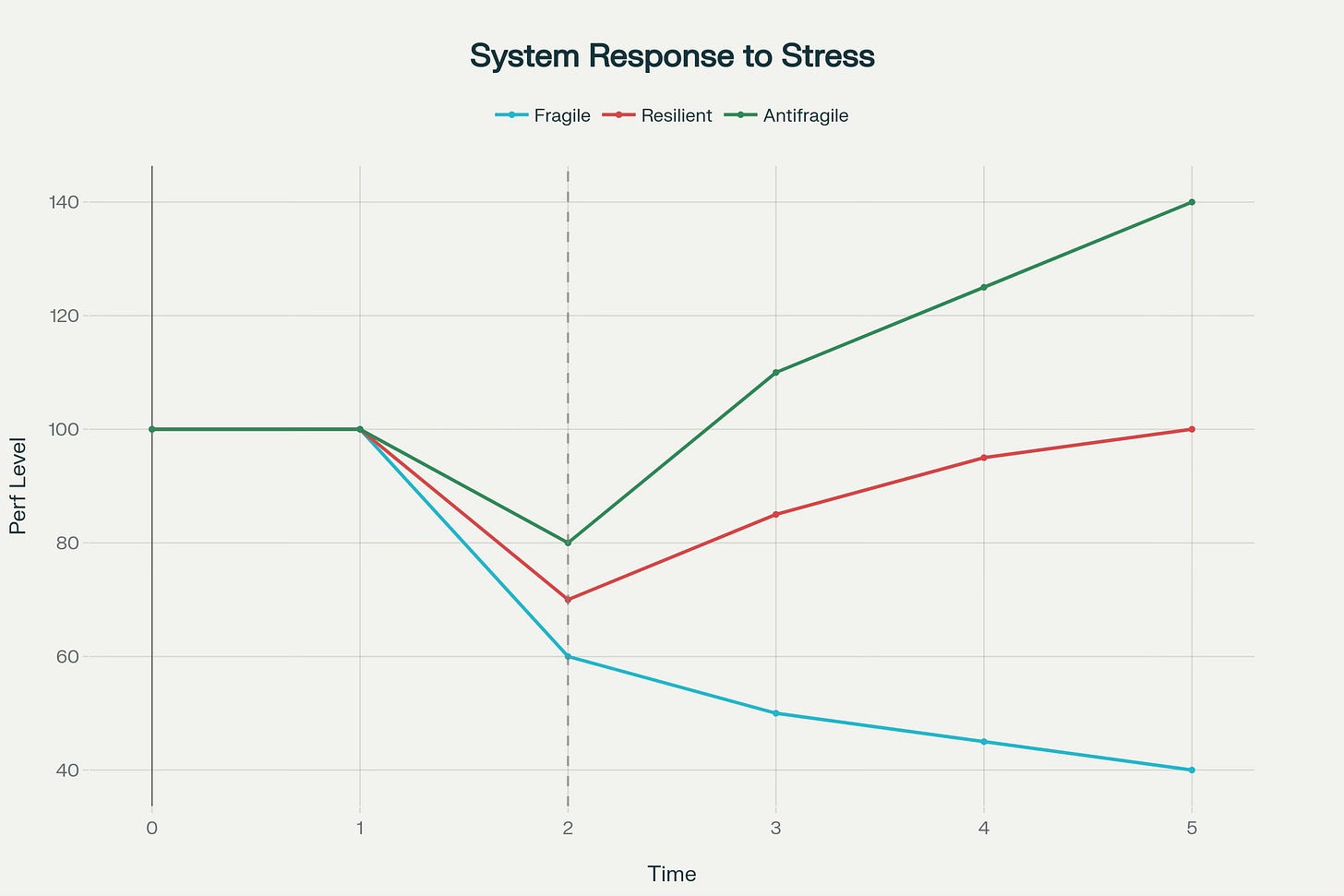

Companies often talk about resilience, the ability to absorb shocks and return to baseline. But in an AI-driven world, resilience is not enough. Systems are so interconnected that a flawed model can ripple across workflows, creating avalanche effects. Operational frameworks like Lean, Six Sigma, and the Balanced Scorecard function as circuit breakers. They standardize, measure, and align, reducing uncertainty and preventing cascading errors.

Nassim Taleb calls this antifragility: becoming stronger through volatility.

“Systems that benefit from volatility.”

Lean’s Kaizen cycles and Six Sigma’s DMAIC method turn failures into feedback. Done well, AI stress becomes a source of learning, not collapse. The difference is not whether disruption occurs, but whether it leaves the firm weaker or stronger.

Systems respond differently to stress: fragile systems break, resilient systems recover, and antifragile systems grow stronger. Operators must design for antifragility so shocks become feedback, not failure.

Self-Aware Planning

Leadership is being tested in what some describe as a perfect storm: geopolitical conflict, climate instability, fragile supply chains, and the uncertain path of AI (Financial Times). Executives feel underprepared, and many respond by avoiding the hard questions. Yet avoidance is costly.

Planning remains indispensable even if plans themselves fail. Eisenhower’s maxim—that “plans are useless, but planning is indispensable”—captures the operator’s challenge. Toyota offers a case study. After the 2011 earthquake and Fukushima disaster, it abandoned “just-in-time” and built a database of 400,000 components across its supply chain. By holding extra inventory and mapping suppliers ten tiers deep, Toyota created the flexibility to survive future shocks, including semiconductor shortages during COVID (Financial Times).

For operators, the lesson is clear: resilience comes from disciplined preparation, not optimism.

Breaking Free of Mimicry

Many AI strategies today are mimicry. Companies adopt tools because peers do, not because they fit strategy. This is what institutional theorists call isomorphism. The result is shallow pilots that copy competitors’ mistakes. Operational excellence prevents this by grounding adoption in differentiated systems.

Without discipline, AI becomes “garbage in, garbage faster out.” With it, AI amplifies strengths instead of weaknesses. Operators must resist the urge to chase headlines and instead build workflows that compound over time.

Even the way companies innovate is shifting. Traditional brainstorming sessions—whiteboards, sticky notes, groupthink—are being supplanted by AI-augmented ideation. Employees now ask AI to refine lists, run trademark checks, and generate options before discussions even begin (The Economist). This doesn’t make human creativity irrelevant, but it does change its role. Operators must design systems where AI provides options and humans provide judgment.

The Operator’s Playbook

The operator’s edge today rests on five principles:

You cannot delegate understanding. AI can draft, analyze, and recommend, but judgment remains human. Goldman Sachs’ caution illustrates this point. Grove’s principle endures.

Culture is behavior. Change comes from visible actions, not mission statements. Octopus Energy and Jamba Juice show how reorganizing teams or auditing values produces real shifts. Netflix’s decision to scrap annual reviews for continuous feedback loops underscores the same point.

Antifragility beats resilience. Systems must get stronger under stress, not just survive it. Lean and Six Sigma convert volatility into learning loops. Taleb’s insight becomes management practice.

Plan without illusion. Toyota’s supply chain reconfiguration shows why planning matters even when plans fail. Operators anticipate shocks, building flexibility into systems.

Workflows before vision. Build the system first; let purpose emerge from what it enables. Too many AI pilots start with grand missions and end in “pilot purgatory.” Operators invert the order. Apple’s smaller AI models are an example: practical workflows before lofty vision.

Each principle is simple, but together they form an operating philosophy suited to the times.

Implications for Operating Founders

For individuals, passion is not a starting point but an outcome. Build career capital, buy autonomy, and mastery will harden into purpose. For companies, design the work. Document the path to “done,” inspect early and often, and let your “why” describe what systems already deliver. For the AI era, resist the temptation to substitute vision for velocity. Build workflows first, then describe the mission they make possible.

Founders face a workforce in flux. Some employees are hugging jobs for security, while others, particularly Gen Z, demand autonomy and rapid advancement. Systems that enable upskilling, mentoring, and multi-generational collaboration will define the firms that thrive. Adaptive HR systems should identify new skills and foster growth, not preserve legacy hierarchies.

AI is the new computer. Like every computer before it, it will not make every business great. The winners will be those who operate well, who embed technology into adaptive cultures, build antifragile systems, and keep understanding at the core of leadership. Operators and Founders should not chase hype. They should design workflows, align culture, and turn a disruptive period into a durable advantage. That is the edge that is there for the taking.

Further Reading

Faith in God-like Large Language Models is Waning, Economist

The Bridge to Our Future Success, Operating by John Brewton - Substack

If you’d like to work together, I’ve carved out some time to work 1:1 each month with a few, top notch Founders and Operators. You can find the details here.

John Brewton documents the history and future of operating companies at Operating by John Brewton. He is a graduate of Harvard University and began his career as a Phd. student in economics at the University of Chicago. After selling his family’s B2B industrial distribution company in 2021, he has been helping business owners, founders and investors optimize their operations ever since. He is the founder of 6A East Partners, a research and advisory firm asking the question: What is the future of companies? He still cringes at his early LinkedIn posts and loves making content each and everyday, despite the protestations of his beloved wife, Fabiola, at times.

this piece beautifully articulates a crucial point: technology is only as good as the systems and culture that support it.

Fantastic article again, thanks John. I love the argument that it is inertia and not technology that fosters (forces?) change. I guess this likely explains why new technology is adapted at varying paces in different companies and locales even if in surface they might look like fairly similar operators?