Operating Economics: This article is part of a weekly series in Operating by John Brewton that revisits foundational ideas from classical economics and applies them to today’s operating environment. Across theory, design, and execution, there is wisdom buried in old economic papers, insights that remain underused by modern operators, founders, and builders. This series aims to surface those ideas, reframe them, and deliver practical tools for Operating in our digital and algorithmic world.

I. Introduction

A store manager cuts staff hours to meet a bonus target. The bonus lands. Service declines, reviews worsen, and repeat business drops.

Nearby, a startup’s algorithm reallocates $2 million across platforms in real time based on performance. There is no bonus, no gaming, just a system optimizing ROI.

This contrast reveals an old problem in new form: the agency dilemma. When one party acts for another, incentives often diverge. Traditional fixes (contracts, KPIs, hierarchy) struggle to keep pace with digital complexity.

Digital tools are reshaping agency. Operating Governance is shifting from static hierarchies to systems driven by real-time data and embedded logic.

II. The Classic Economic Foundations

1. Coase (1937): Firms reduce market friction. Internal coordination can cost less than repeated transactions.

Story: In the 1920s, General Motors began acquiring its suppliers. Too many delays, too much uncertainty. Alfred Sloan integrated production to simplify execution. Coase later explained the rationale: firms exist to minimize external costs.

2. Jensen & Meckling (1976): Firms are contractual systems. Agency costs arise when agents pursue their own goals over those of principals.

Story: In 1985, Jack Welch tied executive pay at GE to stock performance. The goal: align interests. It worked until short-termism set in. Welch later called shareholder-value focus a mistake when applied rigidly.

3. Williamson & Property Rights (1985–1990): Hierarchies outperform markets when assets are specific and control matters.

Story: In the 1990s, Intel depended on custom tools from niche vendors. To mitigate risk, it brought some operations in-house. When flexibility is low, control your wins.

These theories supported the org chart. They suited slower decisions and scarce information. They were built for a time that has passed.

III. Where the Old Model Breaks

The store manager’s bonus plan once worked. Now it invites failure:

Managers chase KPIs at long-term expense

Owners cut costs that hurt durability

Contracts misalign. Metrics mislead

Digital systems operate faster. Feedback loops tighten. Complexity scales. Hierarchies lag. Both agents and principals can exploit slow systems. This creates a design problem for company operators and builders. How do you align incentives amid rapid data and opaque automation?

IV. Emerging Alternatives

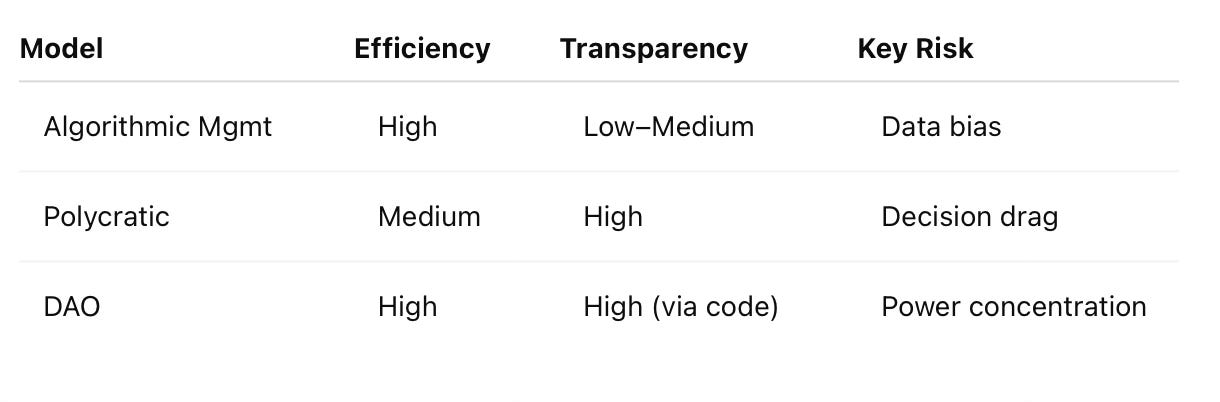

Digital environments demand new governance structures. Each model shifts how authority is distributed, how decisions are made, and what tools enforce alignment. Understanding the terminology is key.

A. Algorithmic Management

Algorithmic management refers to systems where software makes and enforces decisions that were traditionally handled by human managers. This includes assigning work, tracking performance, optimizing schedules, and setting compensation, all centered around access to real-time data feeds.

Story: Uber routes drivers and adjusts pricing in real time. At Amazon, warehouse staff follow task sequences dictated by software. No supervisors, just rules.

Benefits: Speed, consistency, scale

Risks: Opacity, data bias, detachment

B. Polycratic / Collegial Governance

"Polycratic" refers to a governance structure where many individuals or teams share decision-making authority. In practice, this means cross-functional pods that operate with autonomy, coordination, and shared responsibility, often without formal hierarchy. These structures are derivative of matrix reporting structures which are still common in traditional industrial organizations.

Story: Valve employees choose projects freely. At Buurtzorg, Dutch nurses coordinate care themselves. In both, roles shift based on task, not title.

Benefits: Autonomy, adaptability

Risks: Coordination drag, unclear ownership

C. DAOs & On-Chain Governance

A DAO, or Decentralized Autonomous Organization, is a system in which decisions are governed by token holders and executed through smart contracts, self-enforcing rules written into blockchain code. These organizations operate without traditional management, relying on transparent and automated logic.

Story: MakerDAO governs a stablecoin system through distributed votes and rule-bound automation. No CEO. No board.

Benefits: Transparency, consistency, decentralization

Risks: Apathy, power concentration, regulatory ambiguity

D. Quick Comparison

V. Reframing Agency for the Digital Era

The original agency theories assumed agents were people, guided by legal terms, monitored by other people, and evaluated over fixed time periods. Today, decisions flow through dashboards, smart contracts, and predictive algorithms, many of which act without supervision. The “agent” could be a product recommendation model or an ops workflow built on conditional logic. And the “principal” might be a protocol, a KPI dashboard, or a governance layer of code.

What hasn’t changed is the need to align incentives. What has changed is how alignment happens, and how fast it can fall apart. Modern firms must shift from static enforcement to dynamic design. That means embedding purpose into systems, enabling authority to move with expertise and context, and designing governance as an ecosystem, not a chain of command.

Firms now blend:

Code as principal: Software enforces actions

Dynamic agency: Authority shifts by expertise and access

Layered governance: Contracts, systems, norms

New tensions emerge:

Transparency vs. privacy

Speed vs. judgment

Automation vs. discretion

Operators must build systems that flex, align, and endure.

Returning to the Agency Problem

The agency dilemma emerged from economic models grounded in legal contracts, organizational roles, and cost trade-offs. These models (Coase’s transaction costs, Jensen & Meckling’s agency theory, and Williamson’s governance logic) assumed agents were people and controls were legal or hierarchical. These ideas clarified why firms existed and how they balanced incentives.

Today, these assumptions face new conditions. Digital systems operate continuously, optimize at speed, and often behave as agents themselves. Contracts are replaced with code. Roles shift based on data access. The original theories remain relevant, but they must be extended. What used to be a static alignment challenge is now a dynamic one, requiring systems that adapt, learn, and self-correct without breaking trust.

Governance, once about enforcing terms between people, is now about designing resilient systems of coordination between people and machines. That shift requires a new operating toolkit.

VI. Operator Playbook: 5 Actionable Takeaways

1. Design for adaptability

✅ Map workstreams before setting structure

✅ Replace rigid roles with fluid responsibilities

✅ Run periodic org reviews to reflect current reality

2. Update incentives often

✅ Link bonuses to live performance signals

✅ Review KPI frameworks quarterly

✅ Eliminate outdated or misaligned metrics

3. Maintain human oversight

✅ Pair algorithms with accountable owners

✅ Set thresholds where humans intervene

✅ Audit automated decisions for bias or drift

4. Align governance to purpose

✅ Connect goals to company mission

✅ Involve team leaders in metric design

✅ Flag rule conflicts that dilute purpose

5. Stack your systems

✅ Use contracts for baseline expectations

✅ Embed norms into day-to-day rituals

✅ Apply tools that reinforce both

VII. Conclusion

The old model rewarded manipulation. The new model automates intent. But automation alone isn't enough.

As digital systems govern more decisions, the core challenge becomes one of architecture and ethics: Who writes the rules? Who audits them? And how do we ensure that speed doesn't compromise purpose?

Agency is no longer confined to people. It lives in dashboards, workflows, smart contracts, and machine learning models. The organizations that win will be those that design for accountability in both human and algorithmic layers, where governance isn't an afterthought but a strategic design choice.

Final Question(s): If your org chart disappeared tomorrow, would your systems, human and digital, still reflect your purpose? Which part of your company reflects 1976 thinking, and which is ready for 2026?

Recommended Readings & Source Materials

This section provides a selection of foundational and contemporary works cited throughout the piece. These sources explore the origins of agency theory, transaction costs, and emerging models of governance. They are useful for readers who want to go deeper into the academic thinking behind the frameworks discussed here.

“Theory of the Firm: Managerial Behavior, Agency Costs and Ownership Structure” – Jensen & Meckling (1976): Defines agency theory and formalizes the concept of agency costs, including monitoring, bonding, and residual loss, within corporate governance.

“The Economic Institutions of Capitalism” – Oliver E. Williamson (1985): Explores why firms exist over markets when asset specificity and opportunism require centralized control and hierarchical coordination.

“Polycratic Governance in Hybrid Organisations” - Koehne & Ivory (2024): Analyzes non-hierarchical decision-making in hybrid orgs, highlighting trade-offs between agility, inclusion, and performance.

“Principles of Algorithmic Management” – Starke & Broake (2024): Describes how algorithms are used to assign tasks, monitor workers, and manage workflows, with attention to both benefits and risks.

“Economic DAO Governance: A Contestable Control Approach” - Jeff Strnad (2024): Discusses decentralized governance structures using token-based control and smart contracts, with a focus on contestability and incentive design.

Wow! Really great piece, John. This part really struck me:

“Modern firms must shift from static enforcement to dynamic design. That means embedding purpose into systems, enabling authority to move with expertise and context, and designing governance as an ecosystem, not a chain of command.”

The idea of using automation to create a dynamic governance ecosystem that constant optimizes incentives towards key strategic is brilliant. It’s a way to use AI that I hadn’t previously considered. I can’t wait for the next article in the series!